On Planning

How To Accomplish Basically Anything.

I was originally saving this guide for my personal interests but while maneuvering the cold streets of [redacted], I was thinking that I should give this to you guys as a thank you. Am I some planning guru or something? Maybe not, but people have some big flaws in their thinking when it comes to planning and I want help address those.

Let’s get it.

Mentality

Let’s start with mentality, a lot of people don’t understand what they’re trying to do when making a plan. We all know the famous quotes from Eisenhower and Moltke: “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything”, “No plan survives contact with the enemy”. Everyone knows these quotes but don’t really fully understand what they mean.

When you make a plan, your goal should be trying your best to get your plan as close to reality as possible. I say “as possible” because there’s always fog when looking into the future, meaning your plan will NEVER align with reality 1:1. The closer you can get to reality, the higher the likely hood your plan succeeding.

Then why plan at all? Why not improvise all the way through?

Because when you’re planning you’re not only setting a path but thinking through the problem, your capabilities, your opponents capabilities, the obstacles etc. Let me put figuratively, if you planned properly you’re playing chess, if you didn’t you’re playing checkers.

Wait, I thought you said plans don’t match reality?

Yes, there’s a very high probability that at some point in your plan something will not work out. At that point you will be left with creativity and improvisation. The difference between that and just going out and improvising from the start is that you’re following a path that you laid out and you put guardrails around that path. So when it comes time to improvise, you’re maneuvering within a margin that you setup for yourself and you’re more likely to be successful. What?

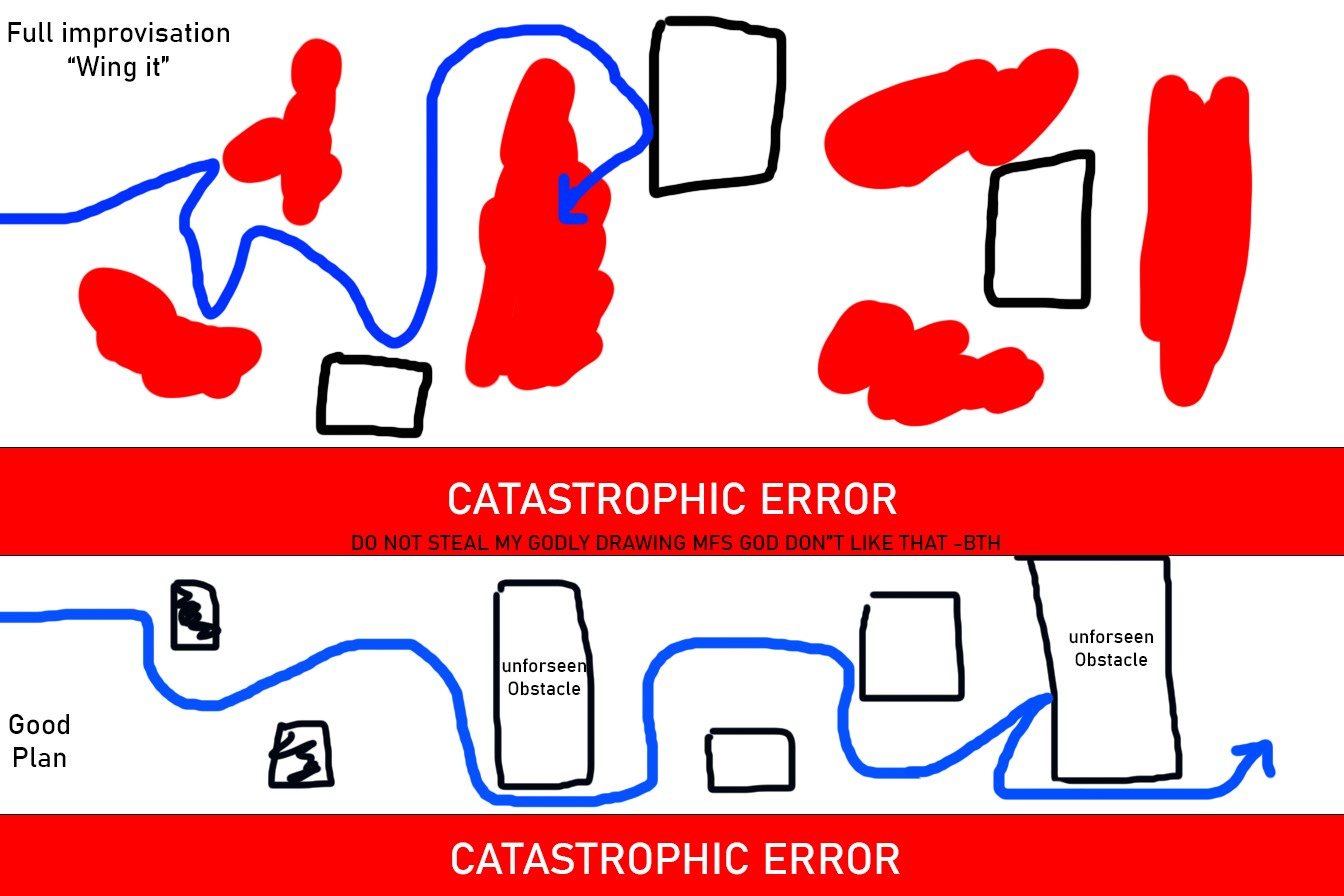

Take a look at my Picasso:

The top part of the drawing is showing you what happens when you just wing it vs when you have a good plan. As you can see when you have a good plan you’re laying out a path and with your research and experience you’re putting down your catastrophic error guardrails and your known obstacles. If you’re smart you noticed that both sides of the drawing have a constant, the improvisation line. Just because you have a plan does not mean you will not have to improvise. You’re actually improvising the whole way but in a more controlled manner. Remember what I said earlier, you can’t map your plan to reality 1:1, your goal is to get close enough. For most people an 80% plan should be good enough. Meaning your plan is 80% reality, the 20% you’ll just have to rely on your creativity and improvisation. This is the baseline but you can adjust based on your risk/speed appetite. Just remember that you should seldom ever try to get your plans above an 80% reality rate. Mapping anything 1:1 with reality is a physically impossible task, that’s how you get “paralysis by analysis”.

Is it getting more clear now mf?

The less your plan maps onto reality the less it looks like that bottom drawing and starts shifting closer to the top.

OK DAM MF HOW DO I MAKE A GOOD PLAN?

Here’s how I would approach making a good plan. First you start with yourself, what do your resources look like? What are your capabilities? This might be an easy question to answer personally but what if you’re planning for an organization? The discovery of resources and capabilities is something you have to be constantly doing. In huge organizations including the military there might be people that can help you in certain ways, but they wont be looking for you to offer their services. You have to find them and talk to them and figure out how they’ll be able to help you when you need it. “Networking” or whatever but don’t call it that, it’s corny.

Second is the actual goal, Identify what it is that you want to achieve, obviously. You should keep in mind that you’re aiming to “win”. What does winning mean? Winning is gaining more than you lost. If you’re standing at the finish line on a pile of all your teammates corpses… Yeah you “won” but in reality you lost everything. Some people will try to cope and tell you something like “What is winning to you?”. This is mostly nonsense that only applies to things like lifestyle, real winning is measurable. We’re not talking about whether you want to live in Texas or Singapore we’re talking about NET GAINS.

Third we get to the actual planning stage.

If you’re working with a team, the best thing to do is have everyone in the room with you when you plan. You do that because when you’re charting your course, there might be realities that others know about that you don’t. You’re just one human, you can’t specialize in everything, you have to put trust in others.

Start doing research, calling people and plotting a rough draft of what you’re going to do. Has someone done this before? how did they do it?

What are the potential pitfalls? What are the most common ways people failed at this? How are we doing to mitigate this? How can we get around this?

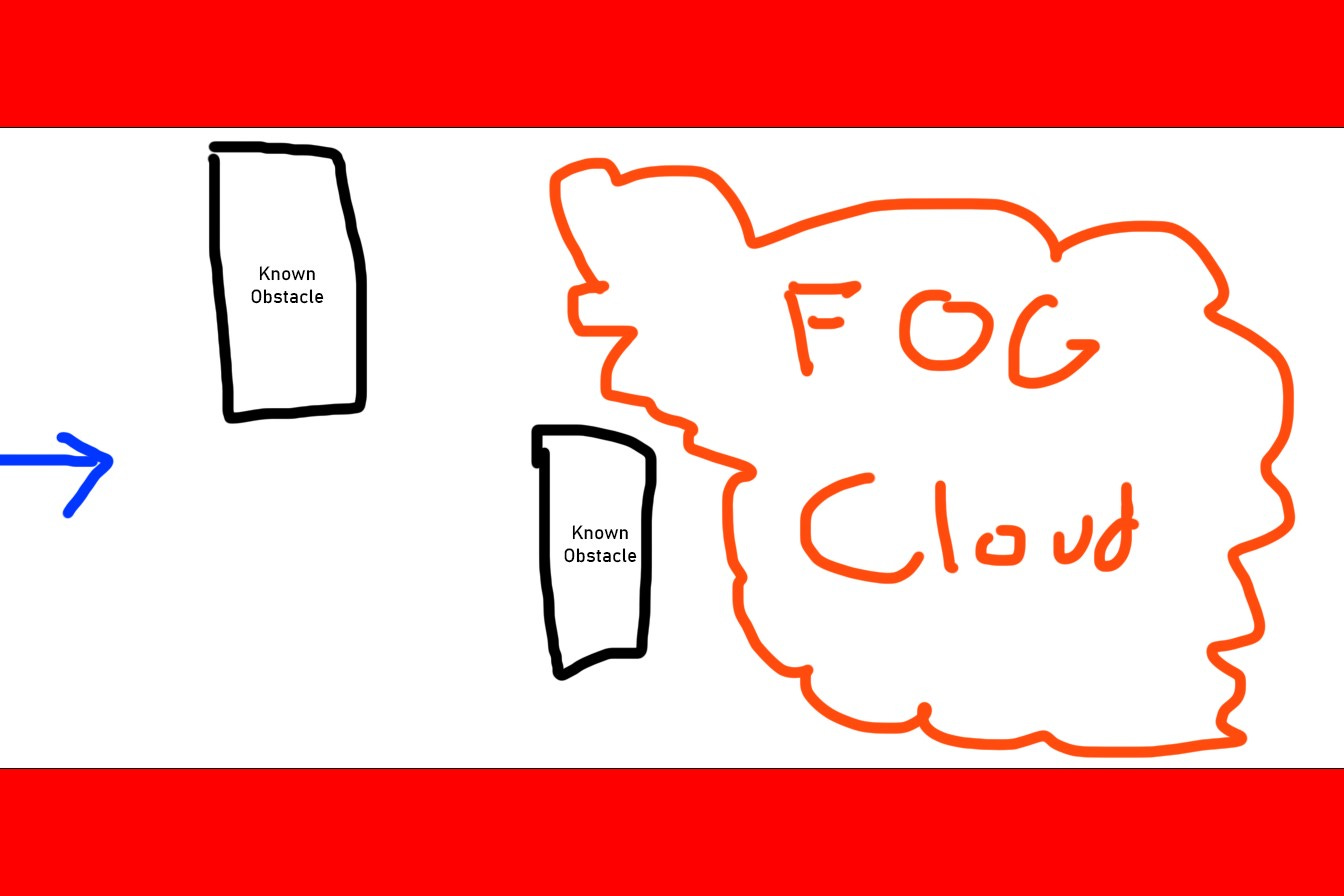

Your plan should start looking like this:

Right now your plan is coming along nicely. You can start executing right now and even succeed, but like I said before we’re trying to reach an 80%.

Note: ALWAYS OVERESTIMATE THE OBSTACLES, YOU ALWAYS OVERKILL

Ok then how tf do I see through the fog?

Well, you want to send some scouts to probe for you, do a test run using the least amount of resources as you can. You need to also define the parameters for a successful test. For exampleBowTied Bull advises, If you’re doing ecommerce don’t get a product manufactured. First make a website and market it so see if people are willing to buy. Even if you’re not in ecommerce this is a good concept to understand.

What you’re doing with a scouting run is giving yourself vision, more data to work with. After your test is done, based on the data you can decide if you want to proceed, create a new test or scrap the whole thing entirely.

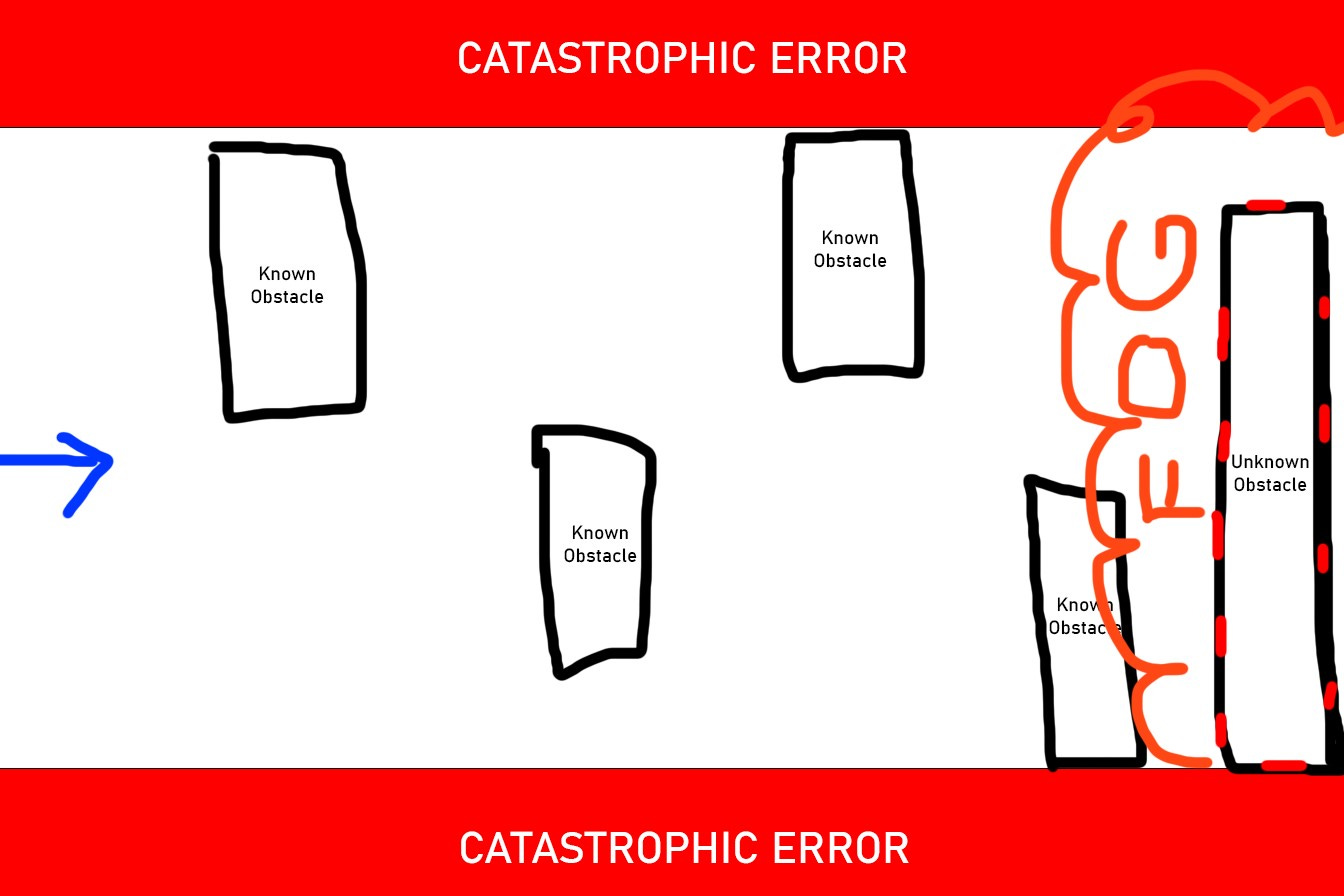

If your scouting run was a success your plan should start looking more like this:

This is not perfect, it’s never going to be but you’re free to run something like this with no fear. You also have to note that just because something is a known obstacle doesn’t mean it can’t kill you. Knowing about something doesn’t necessarily mean you can get around it. You still need leadership, talent, skill and resources. Having a good plan doesn’t help you with those. You as an individual can still suck, this is why I made the first step “looking at yourself”.

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.” -Gucci Mane

Now a few words from a repeat guest and former SOF bro BowTiedBarracuda :

Planning was and continues to be a professional specialty of mine. Entire libraries exist on the subject, on both bookshelves and SSDs, so knock yourself out reading. If I can impart the factor that has been the most useful in combat, business, and in my personal life, it’s this:

Know the “why” and intent.

Why is the most important part of planning. In the .mil-iverse, it’s called “Mission Command.” Some over-educated TED-Talk dude has made an entire career out of it charging F500 companies significant sums to convince (rightly so) executives that they should tell their people the why behind corporate plans.

The United States Army defines “Mission Command” as the “exercise of authority and direction by the Commander using mission orders to enable disciplined initiative within the Commander’s intent to empower agile and adaptive leaders in the conduct of [operations].”

Buzzwords aside, it means that the “why” behind your plan, is key to accomplishing it, just like Hitman explained above in detail. My plan can adapt to the situation when it doesn’t survive first contact. I can improvise, because I know why the plan exists.

Why and intent is just as important with teams. If the team understands why the plan exists, they can take action to adjust, even when the details change. This is what you’d call “intent.” If they understand what we’re supposed to accomplish, bounded by the limits of reality, time, and resources, then they have the flexibility to adjust event when conditions (inevitably) change.

During GWOT a boss of mine gave me the following mission: “Go secure district [x].” I knew the why, and I knew the intent. The geopolitical area was delineated on a map, and the resources available would fluctuate. I had the ROE (rules of engagement), and my team. That’s all I needed. Checklists and specifics can be added by smart team members. The plan can evolve regardless of details.

The above is a positive example of how this works at a middle-management level. The same principles apply at higher levels. A negative example is Afghanistan at the geopolitical/strategic level. What was the end-state? Most senior .mil and .gov leaders didn’t know, despite lying about it for years. And that’s part of the reason things turned out the way they did.

Don’t make the same mistakes for yourself, your business, or your team. Define why, and define the intent.

As always guys, thank you for reading. I’m thinking I might want to make this a series with multiple people adding their own angles. If you got something you would like to add, send me a DM on Twitter.

Note: You can have the perfect plan and all the skill in the world and still fail. Sometimes, life is just bullshit. You have to be able to take that data, recalibrate and attack again. Don’t overextend yourself so that the inevitable hits that you do take are not catastrophic.

This article is a thank you to you guys that support me, Happy Veterans Day.

Thanks for reposting this on X - just subscribed and had not gone through and read all the old stacks. This is excellent.